3. The worldwide race to the bottom

Things always have to keep getting cheaper

In shipping

In 2021, Troy Pearson (43) and Charley Cragg (25) died on the job while towing a pontoon for the mining company Rio Tinto in Canada. The sea was too rough, the wind too icy and their tug too small for the conditions. Yet despite all that, their employer still sent them out. Troy and Charley’s deaths are a tragedy, but not an isolated case.

Crew members on tugs worldwide are being asked to work longer hours for less pay. Some will not be paid overtime. Rest periods are not being respected. Work accidents and near-misses are increasingly common. The nautical knowledge of crew members is ignored. Stress. Fatigue. Indeed, in the tug industry, the pressure on prices is enormous. Everything has to be cheaper and faster.

How does that come about? The tug industry is under severe pressure from unfair competition. Shipping companies form alliances, stand strong and can impose unreasonable rates on towage companies. That results in unsafe and unsustainable working conditions. Tug services are increasingly unable to survive the pressures of lower rates and competition in ports. In Europe, for example, the number of major players has fallen from ten to barely three in less than a decade, and two of them are owned by shipping giants. There’s a clear race to the bottom underway in the tugboat industry. And not just there.

‘These people sometimes stay on board the ships for months on end, without being able to return home. That doesn’t quite smell like force labour yet, but it’s beginning to create something of a stink.’

In aviation

Now let’s take a look at the aviation sector… During the Covid crisis, Australian airline Qantas illegally outsourced 1,700 ground handling jobs. They pretended this was a necessary cost-saving measure, but the unions knew it was also motivated by the fact that outsourced workers could not take industrial action against the company. Comrades of the TWU (the Australian transport union) disputed the issue in court. At the same time, Qantas has not hired any cabin crew directly since 2008, but has instead continued to use 14 recruitment agencies. On 23rd September 2023, our colleagues at TWU achieved a thunderous victory, with the Australian Supreme Court ruling the 1,700 redundancies illegal. Campaigning pays off!

Another example: Avia Solutions Group from Lithuania. This company has a number of brands, including SmartLynx or KlasJet, in its portfolio. In 2021, the Belgian Football Association found it necessary to swap their regular airline (Brussels Airways, which does follow Belgian collective agreements) for KlasJet. Avia hires its crew through an employment agency in the United Arab Emirates, but its aircraft are based in many European countries. The ETF filed a complaint with the European Labour Agency against the firm’s questionable practices.

And then there’s the case of P&O, which on 17th March 2022, unceremoniously laid off 786 seamen via video message, while at the same time simultaneously replacing crew members with cheaper workers from low-wage countries?

In transport and logistics

It was in 2007 that Stefano Gebbia, a Belgian Transport Union militant, spoke at a national meeting with other union delegates. He told the story of Supertransport, the company where he worked as a driver. The company supplied the Carrefour retail chain. He described how management used Hungarian drivers and raised concerns about those drivers’ low wages, longer working hours and worse conditions. He also warned that the practice threatened the employment of Belgian drivers. Just how prophetic the words he was speaking were to be he did not realise at the time.

Supply chains and transport operations, and therefore the people who work in them, are under severe pressure today from the race to the bottom organised by multinational companies. I call them ‘economic employers’: companies that don’t employ their drivers directly, although they are the main client.

Using drivers from Eastern Europe and low-wage countries in Western Europe is a well-known practice. Unions have been denouncing social dumping practices in road transport for years. The only reason behind these practices is to save on wages. And in doing so, all potential means are used: setting up PO box companies, using bogus self-employed workers, flouting (European) laws and ignoring national collective labour agreements. But we are equally well aware that more and more companies are organising social dumping in inland navigation, for example by employing sailors from Eastern Europe. The river cruise industry also takes full advantage of these practices. Dubious temporary employment agencies are often used to employ Filipino drivers or river cruise staff who work for wages well under the pay scales. These people sometimes stay on board the ships for months on end, without being able to return home. That doesn’t quite smell like forced labour yet, but it’s beginning to create something of a stink.

And it goes without saying that social dumping is a real plague in other sectors, too, such as the meat-processing industry and the construction sector. Large-scale institutionalised systems are being set up in many activities where cheap labour is used illegally.

Due diligence directive

It is paramount that these employers are made aware of their responsibilities. They cannot afford to outsource work to subcontractors and yet still pretend that they have no responsibility for what goes on in the transport chain. It’s all about due diligence, which is an extremely important concept. The European Parliament already reached preliminary agreement on the proposal for a European due diligence directive in June. Hopefully, the directive will be in place by the end of 2023.

We should also point out that European integration as a political project is by no means finished. Countries such as Malta and Cyprus and semi-free states such as Madeira enjoy all sorts of European exemptions that rogue crewing agencies eagerly exploit. For example, compulsory social security membership does not apply to workers from Madeira. European seamen sailing under that flag therefore do not accrue social rights. And in Cyprus, although compulsory membership of social security exists for EU residents, in practice this does not happen. And the departments that employ them admit as much. Article four of the European Convention on Human Rights, however, explicitly prohibits any form of forced labour.

A European pillar of social rights should define more clearly what exactly it covers. And despite numerous European meetings on the subject, I feel there has been far too much procrastination for far too long.

‘It is paramount that these employers are made aware of their responsibilities. It’s all about due diligence, which is and extremely important concept.’

Outside Europe, too

What is called social dumping in Europe, by the way, is by no means a European phenomenon. The Americans talk about misclassification. And that appears to be a problem that manifests itself as clearly in the trucking industry in the US as in Europe. Only there, it is US drivers who are being pushed out of the market by the use of bogus self- employed drivers, mostly from Latin America.

Domingo Avalos, one of these drivers, testified in an article in the LA Times as follows: “Most of us come from Mexico or Central America. We are not used to being entitled to use protective equipment in the workplace and most of us do not speak English well. The companies take advantage of this and treat us as second-class workers.”

Drivers work an average of 11 hours a day, six days a week, and are paid at a piece rate per load, regardless of how long it takes to deliver the cargo. Domingo himself did not see too many problems with his status as a bogus self-employed person, until one day he suffered a workplace accident and needed medical attention. The hospital bill soon ran up to more than $2,000. But his employer, XPO, was only willing to reimburse these medical expenses after Domingo brought in a lawyer to handle his case.

Victims: the workers themselves and social security

There’s a clear race to the bottom going on in the road haulage industry. This form of social dumping mainly creates losers: The initial victims are the individual drivers who come from the low-wage countries in question. They work for cut-price wages, put in (too) long working days, do not get enough rest and are often simply exploited!

The second category of victims are the workers in the country where these foreign workers are employed. They risk losing their job because they are too expensive. And their pay and working conditions come under pressure. Why should employers still pay the wages provided for in national collective agreements when they can get workers who are much cheaper?

Finally, it’s the social security systems and tax systems that suffer. Because no or insufficient contributions or taxes are paid on (illegal) labour organised in the black or grey circuit. With dire consequences for the national exchequer. The same problem presents itself for social security, which is underfunded and under pressure from social dumping. Not to mention safety for other road users. Anyone who thinks that this is fantasy on the part of the unions needs to take their blinders off for a moment. Here are some concrete facts to consider:

In February 2013, it became known that Latvia’s Dinotrans was using Filipino drivers en masse. A Dutch haulage company, Martin Wismans, also worked with Filipino drivers. Thanks to the Dutch trade union FNV, strong action was taken at the time and the drivers were protected as victims of human trafficking. Transport Wismans lost its transport licence.

In Padborg, Denmark, five years ago – in 2018 – Danish trade union 3F discovered a camp where Filipino drivers were staying at the weekend. The drivers worked for Danish haulier Kurt Beier, through its Polish subsidiary. The pay and working conditions of those drivers were totally degrading. They earned 2 euros an hour and had to live in a stable that a respectable farmer would not let his animals stay in.

The manager of several Belgian transport companies was sentenced in absentia to one year’s effective imprisonment for human trafficking and social dumping by the Bruges correctional court in May 2022. He allowed foreign drivers bivouac to in degrading conditions in a car park in Zeebrugge. In 2018, he had previously been sentenced to eight months in prison by the Ghent Court of Appeal for similar offences. A number of checks carried out between 2015 and 2018 showed that the owner was using PO box companies in Poland and Bulgaria, according to the labour audit office. However, all the activities conducted by the transport companies took place in Belgium. This construction allowed the accused to circumvent Belgian minimum wages and social contributions. A French official report also allegedly showed that the accused used violence against an employee of the company.

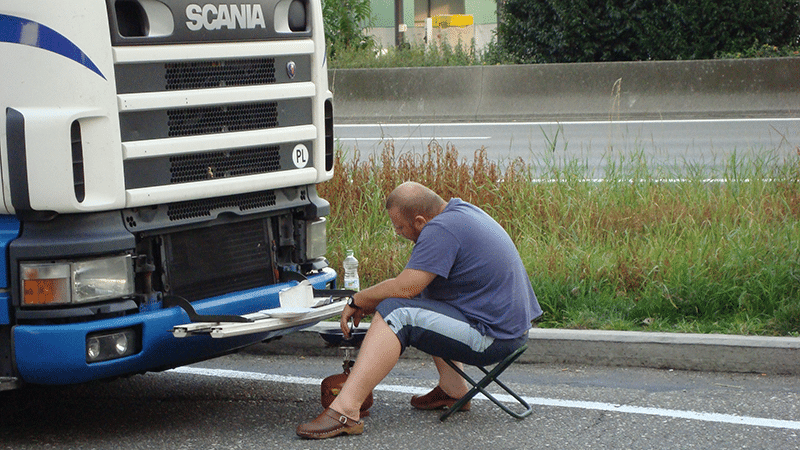

In April 2023, 70 drivers from Polish haulage companies LUK MAZ, AGMAZ and IMPERIA LOGISTYKA – all belonging to the same manager – stopped work. They did so because they had not been paid for more than a month. To draw attention to their plight, they parked their trucks in a car park in Gräfenhausen, Germany, on the A5 near Weiterstadt. It was a historic action that exploited drivers from eastern Europe should lay down their tools for more than a week because they were thoroughly fed up with years of exploitation.

The fact that they were dealing with an employer who did not shy away from employing harsh means became evident when he tried to intimidate the striking drivers with a private militia. Driving around in armoured vehicles and dressed in full combat gear, their job was to threaten the truck drivers and, if necessary, use force to take their trucks away. Fortunately, the police were on hand and managed to settle the conflict in which 19 people were arrested, including the owner of the Polish transport company.

The drivers were driving on behalf of major companies such as IKEA, Volkswagen, DHL, LKW Walter, sennder Technologies and CH Robinson. Which shows once again that multinational companies have an overwhelming responsibility when it comes to exploitation in the transport chain. These economic players hold the key to stopping this exploitation and social dumping. In their race to the bottom of ever cheaper transport, using exploitation and other criminal activities are the only way for them to meet that price that is far too low. This urgently needs to stop.

The summer of 2023 saw a second strike action in Gräfenhausen: more than 120 drivers from AGMAZ, LUK MAZ and IMPERIA LOGISTYKA stopped work for six weeks. It will not be the last strike.

‘I call for a clear European penalty code to be implemented for failure to pay proper wages, as well as for well-defined rules around sleeping arrangements for staff.’

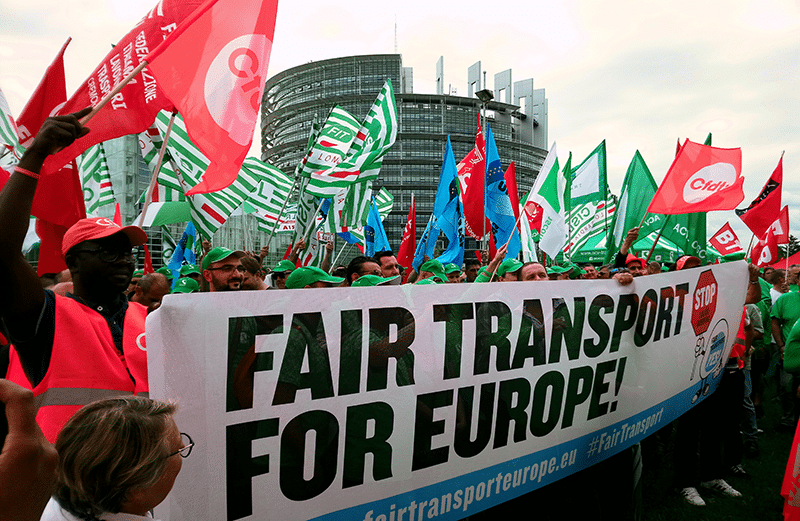

European mobility package and European Employment Authority

After pressure from the trade unions, a European mobility package has been laid down. This means that the excesses of social dumping should, in theory, be better combated. Unfortunately, we can see that these European rules have still not all been transposed into national legislation and that there is far too little enforcement.

It was also through trade union action that former European Commissioner Marianne Thyssen came to set up a European Labour Authority. And although this body is far from being a true social inspectorate as we trade unionists would have preferred, it could become a tool that will help get a grip on social dumping through more and better controls. I also call for a clear European penalty code to be implemented for failure to pay proper wages, as well as for well-defined rules around sleeping arrangements for staff.

It is not only in the transport sector that things are going wrong

The chemical company Borealis was building in the port of Antwerp. They hired the Italian construction group IREM-Ponticelli to handle

the project. Through a tangle of subcontractors, foreign workers were deployed on that construction site. But the Belgian inspectorate services were tipped off about what was going wrong there and took action. Fortunately!

The story of Nasir, Roman and Afrose was one of exploitation, modern slavery and even pure human trafficking. And it isn’t just me talking about trafficking, it’s the judicial authorities in Belgium. 45 Filipino, 30 Bengali and 70 Turkish workers were provisionally recognised by the court as victims of human trafficking. Some Ukrainian workers were also involved.

They were all severely underpaid and certainly did not receive the wages agreed, barely half in fact. They were paid 6.90 euros an hour, just over half the legal minimum wage in Belgium, and much less than what should be paid according to the collective labour agreement in the construction sector. They were housed in appalling conditions and had to work extremely long shifts. Working days of 11.5 hours were the norm.

Borealis, though the client and main contractor, denied any involvement in or responsibility for the offences. When the case hit the press, they terminated the contract with their subcontractor, IREM-Ponticelli, which itself also pretended not to notice. They eagerly shifted responsibility for what was going wrong on to their subcontractors. Legal proceedings are now under way in Belgium, which are likely to take a very long time before final responsibilities are established. But it does illustrate that principals must be made accountable within the entire supply chain.

Making principals accountable

A cool T-shirt for 2 euros. A new pair of trousers for just 10 euros. How can these prices be possible? Because somewhere in Bangladesh or anywhere else in the world, hundreds of workers – often women and sometimes even children – are employed in the most appalling conditions in sweatshops. The tragedy in Rana Plaza ten years ago is still fresh in our minds.

Rana Plaza

On 24th April 2013, an eight-storey building collapsed in Bangladesh: Rana Plaza. The collapse of the textile factory killed 1,134 people out of 5,000 workers and injured about 2,500 people. The collapse of the building is considered the deadliest disaster ever in a textile factory and the deadliest building disaster in modern history. The cause of the disaster was mainly due to questionable business practices and inattention and corruption by management with the aim of maximising profits.

The Rana Plaza factories produced for Benetton, Le Bon Marché, Cato Fashions, The Children’s Place, El Corte Inglés, Joe Fresh, Mango, Matalan, Primark and Walmart, among others. The only tangible effect for workers since the disaster has been Bangladesh’s ‘Accord on Fire and Building Safety’, an agreement on fire and building safety. Under the neutral supervision of the International Labour Organisation, some 200 fashion brands, Bengali trade unions and Global Unions have signed the agreement. That agreement expired in 2021 and will be succeeded by the RMG Sustainability Council, a body concerned solely with building safety. It is something, but it does not address a much bigger problem: the exploitation of mostly working women.

In the meantime, a decade has passed since Rana Plaza, and many have simply moved on with their lives. Unjustly, too, because the British human rights organisation Business & Human

Rights Resource Centre tracked 156 abuses in 124 factories in Myanmar’s textile sector between February 2022 and February 2023. The year before, they examined only 56 complaints. The litany of issues goes on. Their findings: underpayment of wages, unilateral reduction of wages, theft of wages, unfair dismissal and forced overtime. The factories in question mainly worked for H&M and for Inditex (including Zara). Those clothing brands therefore decided to stop their operations in Myanmar after other clothing brands did the same. So no, it is not over, it is not better.

Foxconn

The situation was also dire at Foxconn, a Taiwanese company that is Apple’s main supplier and which manufactures in China. During the Covid pandemic, the company, which has 200,000 employees operated in a closed loop system for months. The company was sealed off from the outside world to prevent internal Covid outbreaks. When infections did occur, employees who tested positive were quarantined without adequate food and without medical care.

Due diligence: towards a fair supply chain

It’s time to look at who organises the exploitation itself. Which means that principals, too, should come under the microscope! Only if the main clients themselves pay a decent price for the services provided can social dumping be stopped.

It is the principal clients who urgently need to pay better rates. Including in the transport sector. As long as they continue to evade their responsibility by continuing to push down rates, only criminal haulage companies that exploit drivers and flout all the rules will be able to keep doing the jobs. It’s high time Europe took a different approach.

Due diligence must become a permanent practice in business and economic affairs. Multinational companies that outsource work must take responsibility for the (mis)conduct of their subcontractors. Is it unreasonable to demand due diligence from the main clients at the top of the tree? Is it excessive to ask large multinationals to clean up their supply chain? To take responsibility for what happens there, even if they outsource their logistics and transportation operations? No, it is not!

There is another reason to bring justice to the transport chain: decent wages and working conditions are in the interest of all of us. The International Transport Workers’ Federation talks about fair wages. A truck driver who has to keep working more and more hours for a pittance is a danger to road safety. For himself and for others.

Urgent action required against modern slavery

The fact that there is still a lot of work to do goes without saying! The International Labour Organisation points out that the global phenomenon of modern slavery has increased in recent years. Specific groups are particularly vulnerable: women, children, migrants without papers, refugees and so on. It’s all about forced labour, sham marriages, commercial sexual exploitation and other horror stories. Another statistic: 12 per cent of those in forced labour are children.

Since the pandemic, we have faced staff shortages in almost all transport sectors. But in fact, it is not a shortage of staff, but a shortage of good jobs. This is the threat facing the sector – but it is also an opportunity for workers and their unions. It gives us a chance to negotiate attractive working conditions and good wages. Transport can never be free. It comes with a price tag. Especially if our goal is to achieve fair transport with secure prices, decent wages and good and safe working conditions. It is also time to convince employers in our sector that good working conditions and decent wages go hand in hand with finding and retaining motivated staff.

°19/09/1973. Belgium.

Doctorate in economics. Researcher and professor in health economics. Former Secretary of State for the Fight against Social and Fiscal Fraud and former President of the Socialist Party of Flanders.

‘Small businesses are also being squeezed out by the competition, until all social links disappear and the only people left to turn to are the expensive law firms of the remaining giants.’

minority grew rich while the majority earned too little. The result was a chaotic society that culminated in the stock market crash of 1929.

The world’s self-proclaimed developed economies were then hit by famine and death. It was only in the wake of this disaster that a determination to change the system was born among the world’s political leaders. Laws were enacted to limit the concentration of the market and power, and the accumulation of capital in the hands of a minority. And above all: wealth has been redistributed. Employee contributions were introduced to insure the population against hardship, illness or disability. Wage costs rose, but a margin was

created so that workers could build themselves up. Social security is only about eighty years old.

At the current time, we are constantly being told that labour costs are bad for the economy. However, if we look at what happened to the economy after the rise in labour costs (redistribution of resources, protection of workers and limiting the power and might of capital), we see that the following 30 years were marked by the highest economic productivity in the world. This period also shows that productivity in Western economies has never been as high as it was when union membership was at its highest. Faced with such a situation, one might think that a new model has been found that benefits workers, the self-employed and entrepreneurs, a model that would therefore be sustainable. All the more so as entrepreneurs and workers have developed the model together.

But what a paradox. Shareholders have abandoned the model with the highest economic productivity, because too much of the economic benefit ended up in the hands of too large a proportion of the population. To a large extent, they even did it to counter entrepreneurship. At the time, wages and working conditions were the only things that were ‘trickling down’. After its creation, the European Union accelerated this race to the bottom by opening up the European labour market in an unregulated way. And it went even further. With CETA, shareholders wanted, when a government regulated for the benefit of the economy, to be able to demand sums from the profits they could not make because of government regulation.

And so it continues. This race to the bottom involves popularising shares so that many people feel concerned when it comes to shareholders. Attempts at globalisation and deregulation continue. The cuts to the extended social model continue. And in many sectors, such as transport, construction and others, this literally means not only that workers are losing out, but that even the smallest companies are being squeezed out by competition. And then it’s the turn of the slightly larger companies. Until all social links disappear and the only people left to turn to are the expensive law firms of the remaining giants. It’s time to establish new rules of redistribution to protect workers and entrepreneurs, and perhaps the latter should write them again together.

°12/07/1968. Germany.

Vice-President of the German trade union ver.di. Responsible for public and private services, social security and transport. Member of the Executive Board of the International Transport Workers’ Federation (ITF). Member of the Supervisory Board of Lufthansa AG and Bremer Lagerhaus-Gesellschaft AG.

‘Trade unions must network with each other, across sectors.’

Trade unions must network with each other, across sectors and nationally like the Vereinte Dienstleistungsgewerkschaft (ver.di) in the Deutschen Gewerkschaftsbundes (DGB), but also within a sector or on the European and international level. Because often the concrete regulations on working conditions are not decided on a national level but on the European and international level. Business strategies, especially of large, often internationally active companies, have long since ceased to be orientated to just one country.

There are numerous examples worldwide of semi-legal and even criminal machinations in the transport sector, but this is also in other sectors. How wages are pushed below the collectively agreed or legal level through bogus self-employment and a lack of clear regulations in employment contracts, often combined with overlong, undeclared working hours and dubious reimbursements for alleged expenses and vehicle damages.

Like the Belgian Transport Union, ver.di fights for better regulations and the enforcement of these regulations at all levels. For example, in the transport sector:

– on the international level in the ITF flag of convenience campaign in maritime shipping;

– on the national level, for example, on the collective agreement on local transport (TV-N), where we are currently preparing for a new round of collective bargaining, together with the climate movement.

This book rubs salt in the wound: demanding that regulations have to be enforced politically – on a company, enterprise, and national level, but especially in the transport sector, also on the European and international level. This is often Sisyphean work, but it is necessary. It is important to constantly monitor the numerous unfair business strategies and to put a stop to them. The strikes of truck drivers from Eastern Europe at the Gräfenhausen motorway service station in Germany, which Frank mentions, were decisively supported by active ver.di participation through the Fair Mobility DGB network, and thus achieved a first victory in which outstanding wages were paid. This shows that the principals of global supply chains play a decisive role as key decision-making points.

Let’s step up the joint fight within the ETF and ITF. Together we can stop the race to the bottom and enter a race for the best conditions.

°12/06/1971. Belgium.

Federal Secretary of the Centrale Générale-FGTB Construction and Wood Sectors. Member of the Executive Committee of the European Federation of Building and Woodworkers (EFBWW). Member of the World Committee of the Building and Wood Workers’ International (BWI).

‘Introducing more investment in social inspection services, plus a limitation on the subcontracting chain and joint and several liability of the main contractor are three legitimate demands.’

Although, during the first waves of postings, the administrative obligations were still guaranteed by the employers concerned, we soon came to notice the emergence of other phenomena on our worksites. There were more and more (bogus) self-employed workers, as well as cases of social dumping and situations that have outright revealed criminal connections.

When a primary school under construction in the Nieuw-Zuid district of Antwerp collapsed in June 2021, the entire trade union movement in the Belgian construction sector was reminded of the reality of the situation. Several people lost their lives in the incident, including some of Portuguese or Ukrainian origin, and some workers were left permanently disabled. Identifying the victims literally took two days. Hundreds of contractors were working on the site, many of them as subcontractors. Most of them didn’t even know what had happened, but they had signed a contract giving them a share in the company they were working for.

Gradually, we also found ourselves seeing more and more third-country nationals on our building sites. People from outside the European Union who, through a Member State, were being given work and residence permits to work in EU countries. The number of posted workers fell again, while the number of workers who were victims of social dumping continued to rise.

Introducing more investment in social inspection services, plus a limitation on the subcontracting chain and joint and several liability of the main contractor are three legitimate demands of the FGTB Construction. Without sufficient progress in these three areas, we will not be able to put an end to the abuses suffered by workers in our sectors.

It was something of a sad awakening when, on the second day of my summer holiday in 2022, the press asked me what I thought about the Borealis affair. In our view, it was never the EU’s aim that workers from, say, the Philippines or Bangladesh, should be working in Belgium for less than half the legal

minimum wage. One of the victims later said that she had also worked in the construction sector in Qatar. She said she was treated better, housed better and paid better there. There is no more blatant example than this to bring a trade unionist back down to earth in Belgium, a country with a unionisation rate of almost 95 per cent in the construction sector.

The solution to this problem will either be European or international, or it will not be at all. Capital, like labour, no longer stops at the borders of a country, a union or a continent. The trade union movement will have to respond to this development at an international level. Retreating to one’s own country or federation will no longer provide solutions.

The action we have taken with the European Federation of Building and Woodworkers (EFBWW) and the Building and Woodworkers’ International (BWI) are unknown to many of our activists, let alone our members. We need to talk more about what we do and, of course, we also need to do what we say. I would like to mention here the example of the BWI Sports Campaign. Can an international tournament still be organised in the future without massive violations of workers’ rights? The BWI and our own Centrale Générale-FGTB federation are putting their finger on the problem, but after Qatar was chosen to host the football World Cup, we shouted for years… albeit into the void. FIFA didn’t want to see us, Qatar told us that everything was fine and the media didn’t wake up to what was happening until about two years before the start of the competition. The same goes for the Paris Olympics and, soon, the Football World Cup in the United States, Mexico and Canada (2026), etc.

This book highlights the problems and challenges, but also proposes solutions and clearly describes what is at stake for national and international trade unionism. In the context of our international activities, time and time again we see that workers’ rights are usually, if not always, the last thing on investors’ minds. So, if trade unions and trade unionists are no longer concerned about the fate of millions of workers, who else will be? We have identified the challenges, now we have to meet them together.